By: Prabowo Subianto [taken from the Book: Military Leadership Notes from Experience Chapter I]

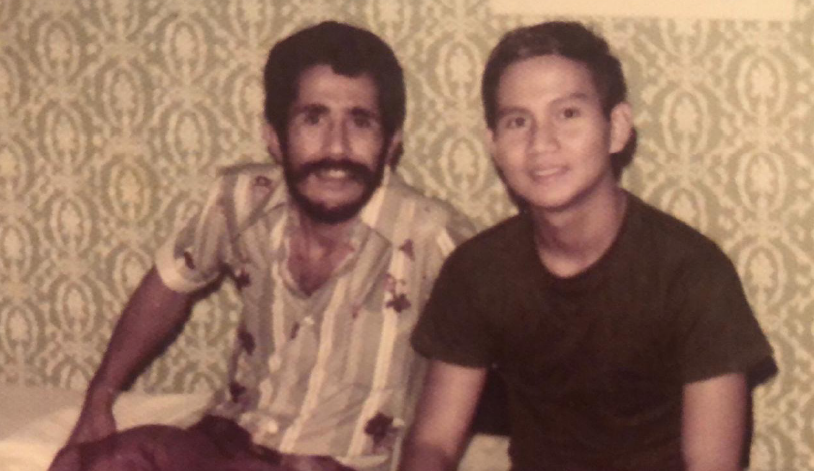

In this book, I feel the need to highlight some exemplary volunteers who fought side by side with the TNI.

Of course, I can only share stories about TNI partisan fighters whom I know and whose track record I have reviewed.

In particular, I want to tell the story of three characters from East Timor who joined the fight with the TNI to defend Indonesia’s honour.

These people were ready to sacrifice their lives, ready to sacrifice their property, ready to leave their village, ready to leave everything they had, to faithfully defend Indonesia.

Abilio Jose Osorio Soares and Francisco Deodato do Rosario Osorio Soares are sons of the leadership of Apodeti Party, a pro-Indonesia political party in East Timor. They were also leaders of pro-Indonesian tribes.

I found out that most East Timorese had long harboured a dream to join Indonesia since the 1950s. This led to a major popular uprising in 1959, centred around the Uato-Lari and Viqueque regions.

The Portuguese, sensing a threat to their authority, cracked down hard, cruelly slaughtering many pro-Indonesian figures and civilians. So, the desire to join Indonesia did not originally start around 1973-1975, but decades prior. Many East Timorese were fed up with the Portuguese colonialism that was oppressive and exploitative towards the indigenous people.

In the 500 years of Portuguese colonisation of East Timor, they did not give much back to improving the land and its people. The Portuguese only exploited the natural resources and cash-crop commodities that were highly profitable for them. The Portuguese also used East Timor as a refuelling base for its naval fleet.

Imagine this, in 500 years of Portuguese rule, there was only one high school in East Timor. When Indonesia set foot on East Timor in 1975, there were only 25 km of asphalt road in the entire province, mostly in the capital Dili. Even in Dili itself, many roads had yet to be paved. Asphalt roads to new sub-districts were only laid after Indonesia took over.

Here, I will not get into whether Indonesia’s decision to liberate East Timor on December 7, 1975, was the right thing to do. I want to tell you that there were people and tribes in East Timor who had wanted to join Indonesia long before 1975.

Among them were the Osorio Soares family. Abilio Soares’ older brother Jose Osorio Soares was captured by Fretilin and killed on January 27, 1976.

Abilio was also captured and nearly executed, but he escaped when he was forced to march from Dili to Aileu. On the way, he managed to escape and join the Indonesian troops.

Francisco Deodato do Rosario Osorio Soares, whom we affectionately called “Ikito”, was also captured by Fretilin in Laclubar and managed to escape by hiding in the forest and finally joined the TNI troops that patrolled the area.

Likewise, his brother Vidal Domingos Doutel Sarmento, a friend from the same area with Ikito and Abilio, also escaped Fretilin’s clutches. A few days before he was to be killed, he managed to escape and join us.

After joining the TNI, they organised pro-Indonesia volunteer forces. In some areas, such as Balibo, many local figures formed volunteer forces and joined forces with the TNI against Fretilin.

That’s the origin of the ‘partisan’, the name we gave to this army of volunteers. They joined without being paid, without being fed, without a decree of appointment, or military education, often without uniforms.

But they were willing to take up arms, shoulder to shoulder, with the TNI because they wanted to be a part of Indonesia. I was impressed, so I include their story in this book to honour the tens of thousands of partisans who were faithful to our cause.

When Indonesia was forced by foreign powers to part ways with East Timor in 1999, they were unwilling to live not under the red-and-white flag. They left their villages. They left their possessions, only bringing what they could out of East Timor. They moved to Indonesian territory, and to this day, they remain loyal to Indonesia.

There are some takeaways here. We ought to learn about their nationalism, their love of the homeland, their commitment to Indonesia, and the principles of the Indonesian nation.

Many Indonesian children have enjoyed independence since their childhood but consider independence as something taken for granted.

Meanwhile, the partisan fighters of East Timor were ready to sacrifice their lives, abandon their properties, and be willing to leave their villages, leave everything to fight for Indonesia.

I think this is such a valuable lesson. I always say that as patriots, we should never forget those who are loyal to Indonesia.

I have to tell you that these partisans from East Timor were true warriors. They were brave, tenacious. They were also physically strong, with good endurance. They were capable of going up and down the mountains, entering the valleys.

They also had a knack for shooting. Maybe it was because of their nature as hunters. They used to hunt in the forest, so they intimately knew the forest and jungle of East Timor. They also had a strong tactical advantage. Their sense of smell was extraordinary. Their night vision was also exceptional. Those are the abilities I saw in these partisans.

Based on the historical accounts of World War II, Australia once tried to recruit them to fight against the Japanese. This is a feature of the tribes outside Java. Many of them have naturally superior military traits.

If we assess them based on the knowledge a cadet is supposed to learn from schools, academies, and books, they often struggle to keep up. If we recruit them into the army, we have to give them special treatment. Perhaps they have no high school diploma, but in reality, they are exceptional fighters.

Let me emphasise once more that their loyalty stands out above everything else. Once they had made a choice, they did not think twice. When Indonesia left East Timor, rather than submitting to someone else’s authority, they chose to leave everything and remain loyal to Indonesia. I am saddened by the fact that for decades they have received little or no attention. Right now, we should be trying to improve their livelihood, especially for their children.