Three years after the launch of the Window, this brief presents some of the main emerging findings from five experimental impact evaluations in The Gambia, Jordan, Burundi, Guatemala and Malawi.

With an estimated 418 million children currently benefiting globally, school meals are one of the most widespread social safety nets in the world.

In 2021, the World Food Programme, in partnership with the World Bank, launched the School-based Programmes Impact Evaluation Window to generate a portfolio of impact evaluation evidence to inform policy decisions and programmes.

Since then, five experimental impact evaluations have started in The Gambia, Jordan, Burundi, Guatemala and Malawi. With the first wave of impact evaluations concluding in 2024, WFP and its technical partners are currently exploring the feasibility of new programmes and countries to join the Window.

This short brief presents some of the emerging findings from the ongoing impact evaluations and articulates the questions and evidence priorities for impact evaluations within the Window moving forward.

BACKGROUND

With an estimated 418 million children currently benefiting globally, school meals are one of the most widespread social safety nets in the world. For many children, it represents the most nutritious – for some, the only – meal of the day. School meals also encourage the poorest families to send their children to school. Once in the classroom, school meals ensure children are well-nourished and ready to learn.

Therefore, school meal programmes are crucial for promoting children’s health, nutrition, education, and learning. While there is already strong evidence that school meals impacts children’s attendance, more evidence is needed on the impact of such programmes on health, nutrition, human capital outcomes, and social protection, particularly from a gender perspective. At the same time, with a global annual investment of US$48 billion in school meal programmes, school meals are increasingly recognised as a key investment to create a stable demand for locally produced food, support the creation of local jobs, and promote more sustainable food systems.

If appropriately designed, home-grown school meal programmes can promote greater demand for smallholder farmers’ produce, stimulate crop diversity, and make communities more resilient to climate change. Many governments are increasingly sourcing food for school meals locally from smallholder farmers with the aim of boosting local agriculture, stimulate crop diversity and increase resilience and climate adaptation. However, empirical evidence on how best to design home-grown school meal programmes and their effects on the local economy is still extremely limited.

3 EMERGING FINDINGS

Three years after the launch of the Window, here are three of the main emerging findings on the ongoing impact evaluations.

I. School meals have a significant positive impact on children’s food security, dietary diversity, and well-being, particularly for girls.

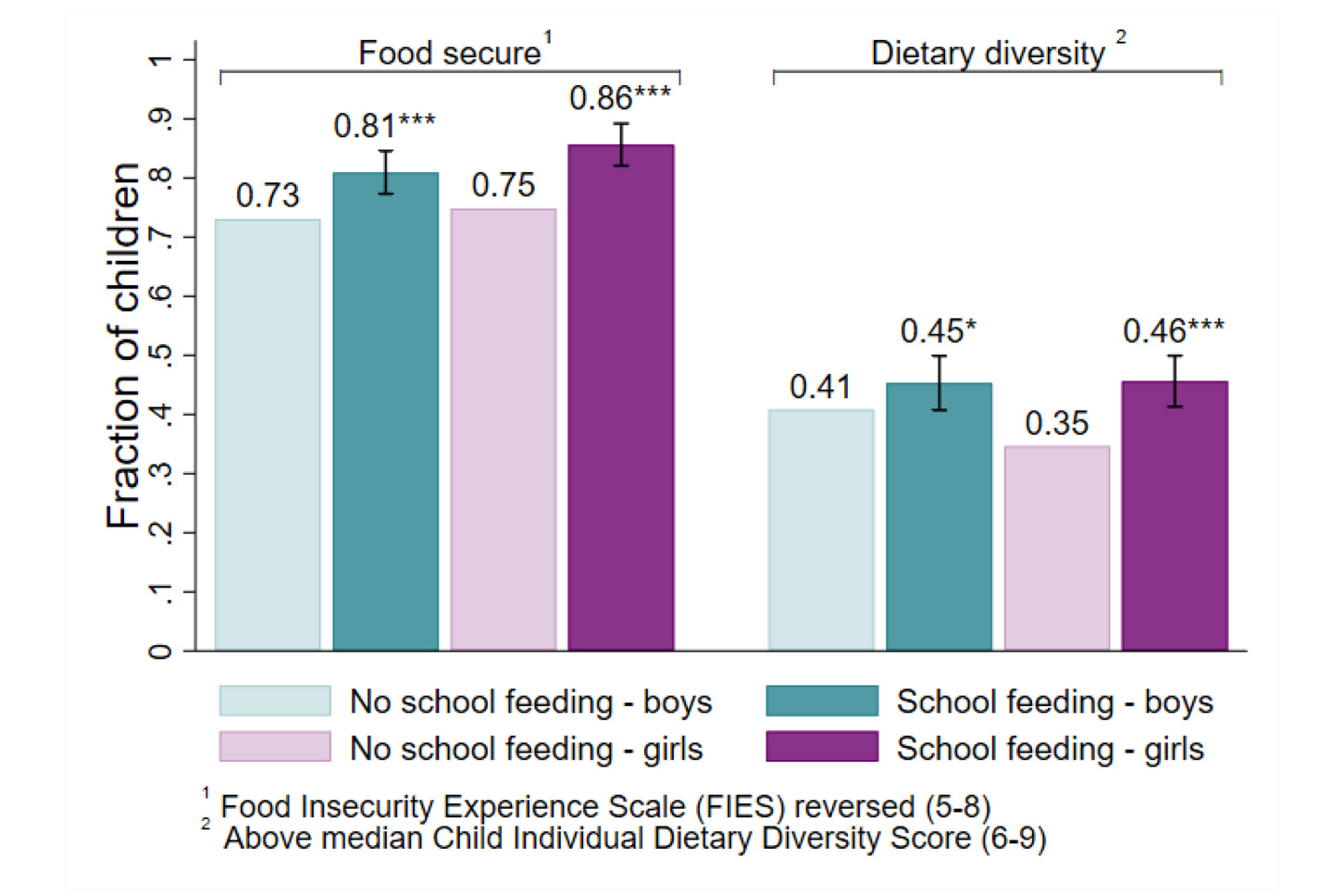

In The Gambia, a randomised control trial compared over 2,000 children in 92 schools and showed how providing a warm meal at school has a significant impact on food security, dietary diversity, and wellbeing indicators such as stress and depression. Evidence shows that girls, in particular, present the biggest impacts as a result of receiving a warm meal.

II. Home-grown school feeding programmes that buy locally can result in more school meals being distributed.

Many governments are increasingly sourcing food for school meals from smallholder farmers with the aim of boosting local agriculture. However, empirical evidence on how to best design decentralised school meal procurement programmes remains limited. Findings from ongoing impact evaluations show that service delivery in decentralised school meal programmes is high.

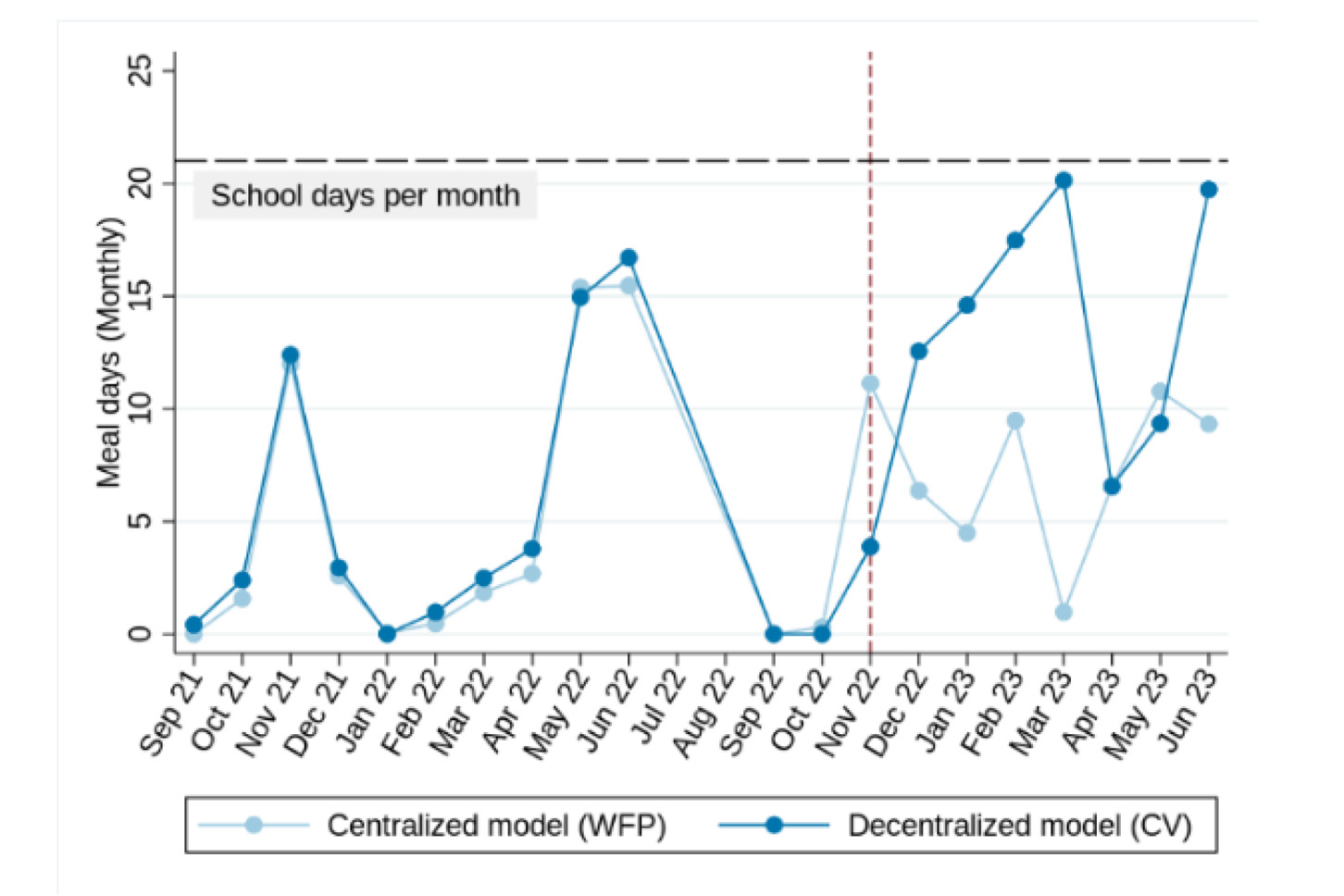

For example, a lean impact evaluation in Burundi compared service delivery outcomes in 50 randomly selected schools that have made the transition to a new decentralised commodity voucher model where commodities are procured from local farmers, against 45 randomly selected schools that remained in the old procurement model where WFP procure mainly from international markets. Evidence shows that the new commodity voucher model was successful in increasing overall school meal days by an average of 75%.

III. School meals represent a significant economic opportunity for workers and local farmers.

Evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Jordan shows that the individual income of women workers more than triples when offered to work in the production of healthy meals in the National School Meal Programme of Jordan. Household income increases by a third and significant improvements in women’s life satisfaction and men’s attitudes towards gender norms are also identified. Evidence from the evaluation in Burundi shows that a significant fraction of cooperatives’ revenues come from sales to schools, showing the significant potential school meals represent for local farmers and cooperatives. Two randomised controlled trials in Malawi and Burundi, which are expected to be completed by 2026, are explicitly assessing the impact of the homegrown school meal programmes on local farmers and the local economy.

MOVING FORWARD

With the first wave of impact evaluations concluding in Jordan, Guatemala, and The Gambia in 2024, WFP is currently exploring the feasibility of new programmes and countries joining the School-based Programmes Impact Evaluation Window. New countries will be accepted into the window for as long as there is demand and a rigorous impact evaluation is feasible. Impact evaluations will be conducted in collaboration with WFP’s technical partners, including, among others, the World Bank’s Development Impact Evaluation department and the Research Consortium for School Health and Nutrition. While specific evaluation questions for each impact evaluation largely depend on country office priorities, it is expected that impact evaluations conducted as part of the window will answer at least one question within the following three areas of interest:

Health, nutrition, and learning

- What is the impact of school meal interventions on children’s nutritional, health, and learning outcomes? How do these effects vary by age and gender?

- To what extent do different complementary activities contribute to children’s outcomes? What is their relative cost-effectiveness?

- To what extent do the benefits of school meal programmes vary throughout the year depending on seasonal fluctuations, shocks, and stressors?

Food systems and local economies

- What is the impact of home-grown school meal programmes on the local economy, including farmers’ income, cooperative revenues, and market prices?

- To what extent can different procurement models be combined with crop and livelihood interventions to support farmers and communities in increasing their resilience and climate adaptation?

Transitions and localization

- What procurement and delivery models are most suitable and cost-effective in supporting the transition to national governments and local authorities?

- To what extent can programmes’ characteristics be optimised? Which ones are the most cost-effective?

Source : School-based Programmes Impact Evaluation Window: Brief